calsfoundation@cals.org

Calico Rock (Izard County)

| Latitude and Longitude | 36°07’05″N 092°08’06″W |

| Elevation: | 462 feet |

| Area: | 4.76 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 888 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 24, 1905 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

401 |

479 |

659 |

738 |

963 |

773 |

723 |

1,046 |

938 |

991 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,545 |

888 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

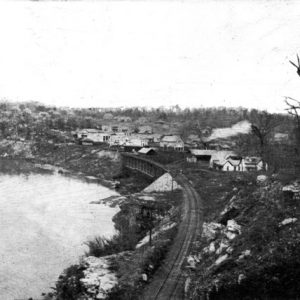

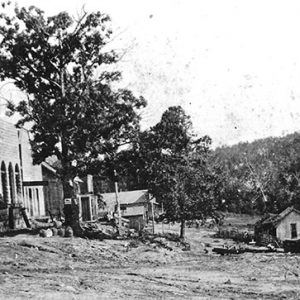

Calico Rock, located on the White River in Izard County, developed as a steamboat landing originally known as Calico Landing. Keelboats had worked the upper White River as early as 1820, followed by paddle wheelers carrying merchandise and passengers from as far away as New Orleans, Louisiana. It became a boomtown in 1902, when construction began on the railroad as tracks were laid along the north bank, beneath the bluffs. The settlement was the headquarters for railroad construction crews. In 1902, the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railway opened rail service there. Calico Rock was the largest town in Izard County through the 1960s.

European Exploration and Settlement through Early Statehood

While the region’s early history is obscure, it was a wild and unsettled region before the Louisiana Purchase. Before it was settled, it already bore the name “calico rocks” because of the wide strips of color—blue, black, gray, red, and orange—giving the appearance of alternate widths of calico cloth on the bluffs bordering the river on the north. No other city in the United States has this name.

Early French explorers took note of the pristine beauty of the river valley, naming the river “La Rivière Blanche.” In writing of his tours of Missouri and Arkansas in 1818 and 1819, author, scientist, and explorer Henry R. Schoolcraft referred to the shore as “calico rock.”

Many Native American artifacts have been discovered in the area. At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, much of northern Arkansas, including this region, was claimed as hunting ground by the Osage tribe, who lived in southern Missouri. They relinquished their claim to this land in 1808, but ten years later it was made part of a Cherokee reservation. The Cherokee generally lived on the southern part of their reservation in the Arkansas River Valley. However, they invited other tribes to join them on their land, and some Shawnee settlements were established in the Calico Rock (Izard County) area. The area’s first white settlers arrived after a new treaty with the Cherokee ended their reservation in Arkansas in 1828; they had a good relationship with the Shawnee, hunting, farming, and trading together. By 1833, though, the Shawnee had relocated to Texas and to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Benge Trail of Tears passed about three miles east of town. The Flood of 1927 unearthed a Native American burial ground immediately across the river from the business district.

Calico Rock’s boat landing was at the river’s confluence with Calico Creek, which flows between the two bluff formations on the river’s north bank. It was the most popular docking site above Batesville (Independence County).

The first post office was established in 1851. By November 1852, the post office closed and was not reestablished until May 1879, with William M. Aikin as postmaster.

In 1857, the first of several stores opened, this one operated by Bartley Kennedy. The same year, Robert C. Matthews opened a store, which closed at the outset of the Civil War.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

While there was some skirmishing in and around Calico Rock during the Civil War, there was considerable jayhawking, including general harassment, stealing, looting, and burning. This, along with the commerce around the boat landing and the arrival of railroad construction crews, caused Calico Rock to acquire a reputation as a tough frontier town.

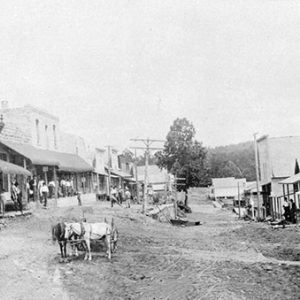

By 1867, Reconstruction had begun. A man named Ellis opened a new general mercantile business in town, followed by Albert Edmonston’s opening a business of his own in 1871. A firm known as Sams & Mayfield put in a large dry goods store in 1873, but it failed after two years. In 1879, the partners Roby and Galloway opened a drugstore, and Kerr and Galloway put in a dry goods store. About a year later, W. E. Maxfield of Batesville added a large general store. By 1885, a mercantile business was begun by Joseph Applegate Schenk (or Schenck) and his partner, a man named Goldman, both successful medical practitioners. These early commercial structures were erected on the north shore, facing the river, with the front street following the river east and west.

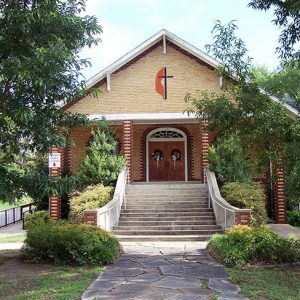

Cotton farms at this time were abundant though small on the thin soil of the region, and there were several cotton gins in the area. In addition, the marketing and shipping of timber products was a major industry of the town. A “barge building” entity operated for a short while on the north bank of the river where the town grew up, though the building of the railroad was the principal factor in economic growth. Churches were slow in coming to the reputedly tough frontier, and religious congregations often met in people’s homes. The Methodist and Presbyterian congregations of the town used the same building until 1907, when the Presbyterians built their own.

Early Twentieth Century

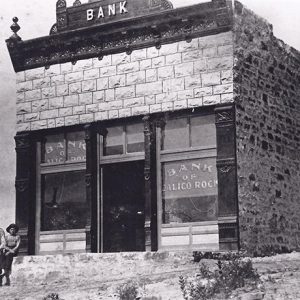

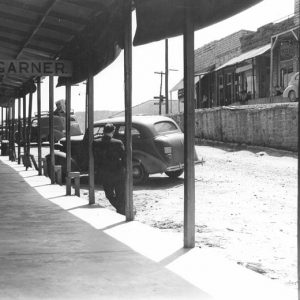

In 1898, a fire destroyed the commercial district, but it became a boomtown in 1902 with the arrival of the railroad. In 1903, Walter Rodman built a hardware store, and the Bank of Calico Rock was built. These two structures are still in use. Steve McNeil built a hotel facility, the predecessor of the present Riverview Hotel built by Ben Sanders.

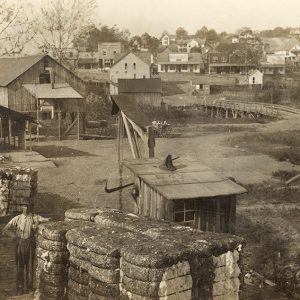

In this rebuilding, the center street ran north and south, perpendicular to the river. The west side was the “upper street,” and the east was the “lower street” because of the split elevation. Because the west side was much higher, a rock terrace wall was erected down the middle of Main Street.

On April 7, 1923, a spark from a locomotive on the switch track set fire to a warehouse. Winds spread the flame to Main Street. Over twenty businesses were destroyed—all of the commercial structures on the east side and some on the west side. The brick and stone replacement structures remain.

Before the Norfork and Bull Shoals hydroelectric flood-control dams were built upstream from Calico Rock, flooding from backwater on the creek was frequent, especially in the basements of businesses on the lower street elevation. The floods of 1916, 1919, and 1927 were particularly devastating.

For many years, Calico Rock was the largest town in Izard County. It was the first town in the area to have electricity, as Herbert William Wright erected an electric generating facility and installed an ice plant. In 1935, the city installed a water system.

World War II through the Faubus Era

During the World War II years, the economy of this already struggling town was hit hard. There was a great deal of out-migration to Sunflower, Kansas, by people seeking employment in an ammunition manufacturing arsenal located there. After that plant closed, many former residents of Calico Rock stayed in the Kansas City area, and their families often followed them there. About the same time, there was a noted migration of residents to work in the orchards of Wenatchee, Washington, gathering apples, pears, cherries, and other fruit.

Modern Era

The town’s population has remained fairly consistent since the 1950s—although the population increased from 991 in 2000 to 1,545 in 2010. Calico Rock has never attracted much industry to sustain it. Since the 1960s, neighboring towns have grown faster. However, served as it is by two state highways, 5 and 56, with a highway bridge erected in 1967 on Arkansas 5 over the White River, replacing the historic ferry, the town has proven very attractive to tourists and retirees. It is located approximately fifteen miles south of Norfork Dam and Lake, fifteen miles north of Blanchard Springs Caverns, and a short distance from the Buffalo National River; it boasts its unique calico bluffs situated on the beautiful White River with its renowned trout fishing. It is also adjacent to the Ozark National Forest and its mountain ranges and streams, and Calico Rock features a number of quaint shops on the historic Main Street.

Education

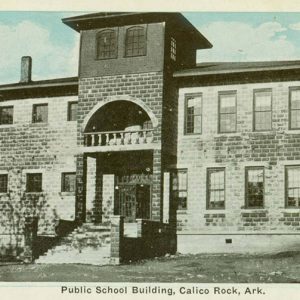

The earliest school in the area was established late in the 1870s at Spring Creek, about three miles east of town, and was known as the Spring Creek Academy. J. A. Kerr, a highly respected educator, taught there. The town’s first schoolhouse was built in 1903. In 1921, the town built a two-story concrete block structure to house the elementary and high schools, and it served for about fifty years. The town now has a separate grade school and a junior and senior high school.

Industry

Agriculture was the base of the region’s economy. Cotton was the main crop from the early days to the early 1940s, replaced by beef, poultry, and related agriculture. The steam cotton gin arrived in 1882, owned and operated by Andy Killian. (Earlier, Robert C. Matthews had built quite primitive gins powered by a “tread wheel” turned by mules or oxen walking on a tilted wheel platform.)

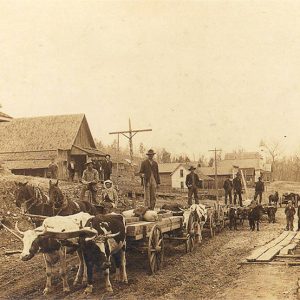

The sawmill industry and the marketing of timber figured heavily into the economy by the 1880s. A planer mill complete with dry kiln chambers was part of the economic development by 1904. Robert Hays and his brother converted it to a hardwood-flooring mill by the 1950s. It was not uncommon by 1907 to see more than 100 wagons arriving daily with timber products. The Benbrook Flour Mill, a water-powered corn-grinding mill, contributed to the region’s economic strength. Hence, Calico Rock became quite a shopping center as farmers brought their produce and did their shopping, frequently from such distances that they would camp overnight in the wagon yard, known still as “Peppersauce Alley” because of the moonshine whiskey traded there.

Notable Figures and Attractions

Dr. Henry Harlin Smith, a resident of Calico Rock, founded one of the largest and most popular string bands in the 1920s: Dr. Smith’s Champion Hoss Hair Pullers. The Calico Rock Museum and Visitor Center opened its retail space in 2010 and its exhibits to the public in 2011. The Calico Rock Home Economics Building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Brooks, Audrey Garner. “A History of Calico Rock As I Know It.” Calico Rock Progress. October 1967.

Gentry, W.M. “Calico Rock and North Izard County from 1883 to 1914.” Calico Rock Progress. June 1956.

Jeffery, Augustus Curren. Historical and Biographical Sketches of Early Settlement of the Valley of the White River Valley Together with a History of Izard County. Richmond, VA: Jeffery Historical Society, 1973.

John Quincy Wolf Sr. Papers. John Quincy Wolf Folklore Collection. Regional Studies Center. Lyon College, Batesville, Arkansas.

Mitchell, Steven D., ed. Calico Rock: A History from 1831–1966. Calico Rock, AR: Calico Rock Museum Foundation, 2012.

Perryman, Reed Mack. “History and Development of Calico Rock.” Izard County Historian 15 (April 1984): 21–29.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Schoolcraft in the Ozarks; a Journal of a Tour of Missouri and Arkansas in 1818 and 1819. Edited by Hugh Park. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1955.

Shannon, Karr. A History of Izard County. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithographing, Co., 1942.

Wolf, John Quincy Sr. “Early History of Calico Rock.” Calico Rock Progress. February 1943.

Ed Matthews

Little Rock, Arkansas

My grandfather, Ewell Seay, was born in Calico Rock in 1910. My grandmother, Vivian Lyndsey, was also born in Calico in 1917. My young life was full of stories of Calico Rock. My grandfather was a great storyteller. I’m very interested in Calico Rock here recently. I’m searching for anything online pertaining to it. I long for a visit; it’s been forty years since my last.